Objects and Memory

Written by

By Mark Amery

Music and memory are close companions. Personal moments can come flooding back at the sight of an album cover. Yet the way we listen to music has shifted continually in recent decades, from the 45 record through to the MP3. Boxes of vinyl records and cassette tapes, which even to look at come embedded with emotion and rich with histories, have often been consigned to the garage. With recorded music comes an uneasy tension between its importance as art and personal memento and its disposability as a commodity.

All of this makes for rich ground for artists to explore. Yet the current exhibition at the Adam Art Gallery touching on this theme, Object Lessons seems strangely muted and confused. There are strong ideas running through it, but it’s rather austere and oblique given the charge of its theme. It’s as if in considering such fertile territory it’s got stuck in the groove of static between many different tracks of thought.

Curators Laura Preston and Mark Williams talk of one starting point for thinking about the show as the history of record label Flying Nun. Another, the urban legend of how in 1987 the only vinyl record press in New Zealand was thrown into Wellington harbour to push the move to the compact disc.

This is great material, and New Zealand has an impressive history of independent music production and distribution (well beyond Flying Nun), providing an underappreciated artistic legacy in music, film and art. And while you don’t go to a gallery expecting a history show, Object Lessons feels numbed by the memory of the past rather than charged by it.

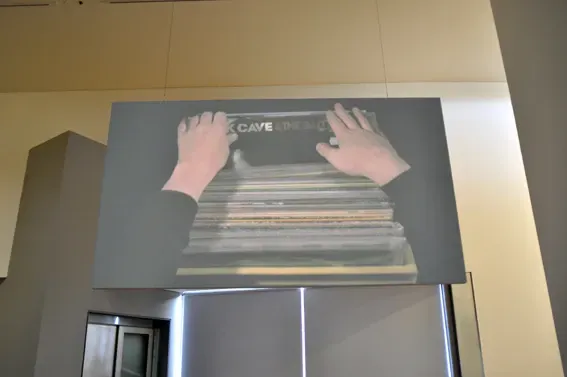

Providing a strong opening, in Caroline Johnstone’s video work we watch hypnotically a pair of hands move carefully through a crate of records examining one cover after another. The catalogue of music matches the listening habits of an independent record buyer of the 1980s, when second hand vinyl stores were arguably at their peak. Time has been slowed, and when the hands reach the far end of the crate the film runs backwards through again to the front, the hands seeming in this mesmeric movement to hover over the covers as if reading them in Braille. This matched by an abstraction of the sound of 2010 – the drone of vuvuzela. The work provides a beautiful evocation of the overwhelming fuzz of overlapping time that is locked into a crate of records, and the power these physical objects have as magical talismans (as Bruce Russell describes them in the catalogue).

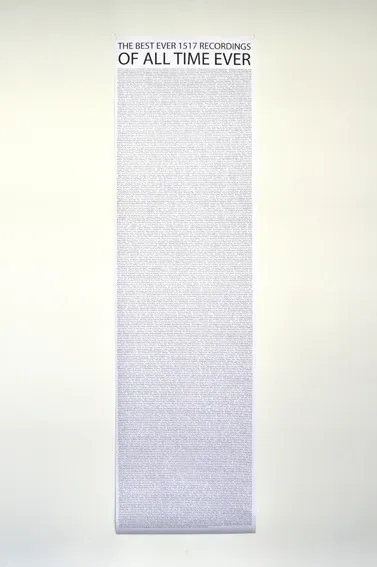

DJ $1 Record (aka Bryce Galloway) presents photographs of the covers of CDs bought on the cheap from second hand stores (complete with the receipts), plus a soundtrack of the mix CD series he continues to compile from these sources. It’s a smart personal intervention into the cycle of musical consumption, but I found it uninvolving as art. I missed the physical object, and the directness of the wry suburban humour and wiry figures of Galloway’s drawing and musical projects. In the gallery window meanwhile is a list of ‘the best ever 1517 recordings of all time’. The selection is as random and idiosyncratic as the number - a nice dig at our attempts to catalogue the past.

Torben Tilly and Robin Watkins move this interest in time into a metaphysical space that echoes the forward and backward rocking motion of Johnston’s work. An elegantly austere arrangement of objects, sound and video creates a place of stasis between things, balancing the different weights of existence in a way that echoes the balance between the needle in the groove and the counterweight on the end of a turntable arm.

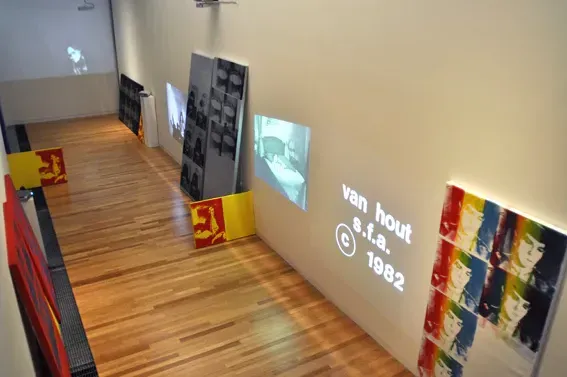

Ronnie Van Hout has re-presented imagery and sounds from his own early work as an artist with the early Flying Nun scene. Record artwork is reproduced as Andy Warhol style screenprints (a nod to this scenes debt to the Velvet Underground and Warhol’s attendant Factory). These punctuate the space alongside video of bands like The Pin Group and Gordons labouring away at their instruments. Another film shows young women engaging in a pillow fight, their voices and the sound of The Clean’s ‘Tally Ho’ part of a muffled soundtrack, as if the past was now a never-ending party going on in another room while you sleep. I like the evocation of memory here, but the work ultimately feels like an artfully fragmented glamorisation of what has gone before, unresolved as a new work.

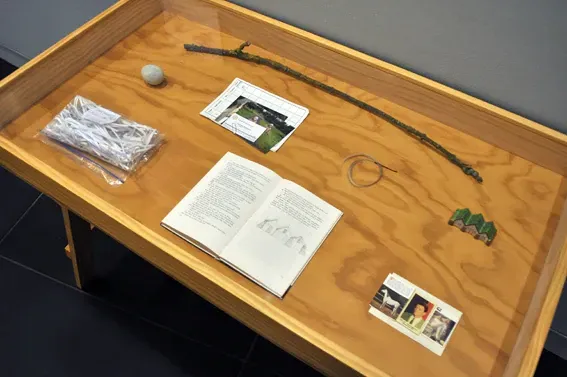

My favourite work is by Fitts and Holderness. A brilliant, fresh introduction of the documentary into art, its connection to the exhibition theme nevertheless is too indirect. Also dealing with memory as embedded in objects and people, the artists reopen the case of a girl who went missing in Iceland in 1997, conducting interviews with people connected to the case, presenting portraits of these interviewees, a display case of relevant objects and, in its own display case, a compelling symbolic object relating to the disappearance, a pine cone embedded with broken glass.

It’s a work that fits more strongly next to the exhibition at the Adam by 2010 Turner Prize nominated collective The Otolith Group. They comment rather poignantly: “For us there is no memory without image. And no image without memory. Image is the matter of memory.”

Object Lessons: A Musical Fiction, Adam Art Gallery, until 10 October